Crowds enjoy the solar eclipse in Maine. Source: Maine Public Radio

On April 8, across New England, it started around 2 p.m. and increased for several hours: The darkening of the sky and the ramping of the region’s natural gas plants. The 2024 solar eclipse inspired awe, excited millions, and required careful planning by the region’s power generators and grid operator to ensure the continued reliable delivery of electricity. The eclipse also illustrated the tremendous evolution underway in New England’s electric grid and the complexities of operating that grid. It underscored the need not only to build new power plants but to retain many of the ones we have — many of the same ones that saw much action on a notable spring day.

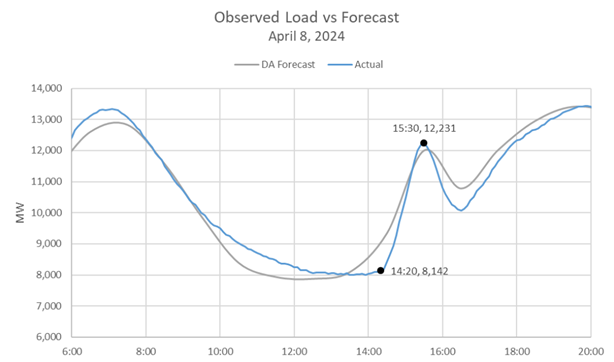

The 2024 solar eclipse significantly reduced the ability of New England’s roughly 350,000 individual solar arrays to produce electricity. According to ISO New England, April 8 would seem like a normal day, but-for an undetermined loss of solar power and subsequent surge in demand for electricity in the afternoon. The ISO needed to ensure that non-solar generation could meet that surge in demand, and generators across New England were on notice to be ready to run.

The results were record-setting. The increase in demand for electricity from the grid was the single largest observed 60-minute ramp on record in New England, at approximately 4,000 MW – double the typical maximum.

The eclipse demonstrates a new kind of reliability challenge as the grid transitions to a decarbonized resource mix. For many hours of the day, weather dependent resources can meet the needs of millions of homes. However, there are events that are out of human control that will require a different resource to perform. Happily, the where and when of solar eclipses have been known for centuries. Other events, less so.

For the foreseeable future, there will be circumstances that will require grid operators to rely on more traditional, existing resources. Those circumstances will offer less warning and last longer than an eclipse – such as an extended cold snap.

The observed load increase of ~4,000 MW over a 60-minute period during the eclipse is the largest observed 60-min ramp on record in New England. Typical maximum observed 60-minute load ramps range between 2,000 – 2,200 MW. (Source)

On April 8, when solar power fell off, much of the replacement generation came from two sources: Natural gas power plants, which collectively increased output by more than 2,700 MW, and from Canada, which went from pulling north nearly 600 MW of electricity from New England to exporting about 700 MW.

As the eclipse ended around 3:30 p.m., solar units began to generate again, and the other power plants ramped down. And then, predictably, the sun began to set. At around 4:30 p.m., power plants across the region started to ramp back up again, only this time more gradually, peaking around 8 p.m. – when demand decreased again as millions of people headed for bed. Even though there was no extreme weather, the region’s power plants had to significantly ramp up and down to maintain reliability through the day.

April 8 was an unusual day for the electric grid, but a manageable one: We knew well in advance that it would happen. The event had a relatively short duration, and there were plenty of resources available to pick up when solar units temporarily went off-line.

But the fact is, the grid operates through a wide range of contingencies, and not all of them come with lots of notice or short durations. In fact, the opposite is true: We live in a time of increasingly extreme, frequent, and unpredictable weather events, and we need to ensure that we have the right resources available for the events that offer little notice and prolonged durations. ISO New England has been developing modeling tools that have shown there could be prolonged periods of low output from renewables in the winter, a circumstance that underscores how important it is to retain the resources that can provide those critical reliability services. For the foreseeable future, that takes the form of many of the facilities online today.

As solar output ramped down, energy from imports, natural gas, and hydro ramped up. Imports into New England increased by ~1,200 MW during the peak of the eclipse. (Source)

In New England’s legislatures, most energy conversations are about the need to increase the deployment of new, renewable generation resources and related infrastructure to meet increasing demand and the realities of climate change. And we will need way more clean energy to come online in order to meet growing demand from electrification of transportation and heating. But that’s only part of the story.

Current policies ignore the fact that, right now, nearly half the region’s energy annual energy demand is already met by non-emitting resources, including nuclear, hydro, solar, and wind. These resources are workhorses that millions of us rely on every day but do not receive the same attention or fanfare as new, renewable resources. This is a shame: On April 8, it wasn’t just natural gas that ramped up as solar dropped off, but wind and hydropower as well.

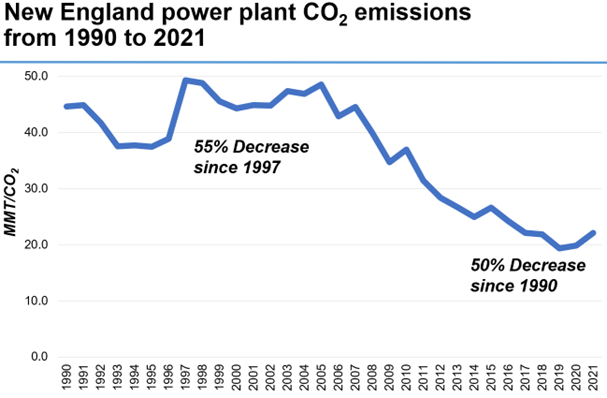

For years, New England has benefitted from significant emissions reductions from the power generation sector – a 50% reduction since 1990. That is because of the existing zero-carbon plants as well as dramatic efficiency increases at fossil fuel facilities. We now have one of the cleanest power generation fleets in the entire country. That is something New England is rightfully proud of.

New England’s existing generators are the foundation on which the clean-energy future will be built, and we must protect them to ensure that foundation is strong enough to withstand the demands of extreme weather wrought by climate change and the demand growth driven by electrification. The new, renewable resources the New England states are pursuing are ones that will add to, not replace, many of our existing generating facilities. This is a logical reality, not theory or ideology: New England could need roughly twice as much electricity in 2050 than it did in years past, and we need to build gigawatts of new generation just to keep pace with the forecasted load growth. In addition to those existing low-emitting resources, New England will also continue to need many of its existing fossil-fired plants for key times when the weather is uncooperative — at least until other technologies emerge that can fill this gap. The truth is, if we let too many of our existing resources retire, we run the very real risk that we will compromise the reliability of the grid.

Source: Energy Information Agency, released July 12, 2023

The stakes are high: As important as reliability has always been, it will become even more so as more and more businesses and families convert their heating and transportation needs to those powered by electricity. For people to make these changes, they need to have faith that their electricity is reliable and that they can afford their bills.

We cannot tolerate a reliability failure. Nor can we take for granted the critical role of under-appreciated power plants that continue to meet the region’s electricity demand.

Most of the region’s existing resources rely on the wholesale electricity markets to sustain their operations. However, those markets do not currently compensate existing resources for their full reliability and environmental contributions. To its credit, ISO New England has begun to address the reliability impacts through its Resource Capacity Accreditation, Prompt-Seasonal Design, and Day Ahead Ancillary Services projects.

But efforts to support and compensate the environmental attributes of existing resources are mostly scattered one-offs, usually with different state legislatures contemplating varying lifelines for certain preferred resources. Or, sometimes not at all. This is inefficient and, over time, runs the risk that the critically needed existing resources will have investment dry up.

It is far, far past time for a collective effort to chart a more efficient way to continue to drive down emissions and support reliability. We strongly believe it can and should be done through a mechanism at the wholesale level, which would prioritize reliability while fostering innovation. New England has a strong track record of collaborating across state lines to increase competition and protect reliability. But New England is also a notoriously difficult region in which to build new infrastructure and the clock is ticking for some of our existing plants, with just about 3,000 MW planning retirements over the next few years.

At NEPGA, we have long called for a meaningful price on carbon, as have others. There have been alternative proposals worthy of consideration, but the overall effort has not yet yielded meaningful gains.

Regardless of the method, something needs to change. And this isn’t just us saying so – diverse stakeholders like ISO New England, and even some states, acknowledge that the status quo is the wrong long-term path.

Some have observed that, in New England, new electricity supplies often come online later than planned – sometimes years behind schedule – but retirements pretty much always happen on time. It is a lot easier to maintain existing facilities than it is to create new ones. In New England, we need to do both.

Time is of the essence. According to NASA, the next total solar eclipse visible to the contiguous United States will take place on August 23, 2044. And while that may be a ways away, we know that there will be plenty of other moments of stress on the system between now and then.