Do you have a heat pump? Policymakers across New England want you and all of your neighbors to get one. And an electric vehicle, while you’re at it. Over the next two decades, the people and businesses of New England will be using more electricity than they ever have in their entire history.

The scale of the infrastructure we need is so large that it’s hard to actually picture.

Our region is currently home to about 400 conventional generators, but, according to ISO-NE, we expect to host more than 1 million weather-dependent generators by 2040 to meet state policies. In the same period, New England would go from 6,000 MW of installed solar to 28,000 MW, and from about 1,400 MW of wind to an additional 17,000 MW of offshore wind.

We need to actually build these things for this future to become a reality. But in New England, news articles are usually about opposition to construction, not the embrace of it. Our region is notoriously heavy on “NIMBYism,” i.e., “Not In My Backyard.” In fact, there is now a whole nomenclature of acronyms for this statement – BANANA (Build Absolutely Nothing Anywhere at Anytime), NOPE (Not on Planet Earth), NIMTO (Not in My Term of Office), etc. This holds true for just about any new infrastructure, particularly when that infrastructure is about producing energy. And it’s not only for fossil-fuel projects but renewable energy, transmission lines and substations, and battery storage projects. If we’re serious about our legally-mandated climate goals, we need to transform ourselves into a bunch of “YIMBYs.” I.e., “Yes in My Backyard” types. That’s a big switch. But we can get there. We have to.

If we’re serious about our legally-mandated climate goals, we need to transform ourselves into a bunch of “YIMBYs.” I.e., “Yes in My Backyard” types.

First, it helps to remind ourselves why we have chosen this path: Because we want a healthier environment and less dependency on imported fuels. By switching to electric vehicles and non-fossil-fuel heating and cooling, we will lower the two leading sources of carbon emissions in our economy. And with that will come other benefits, such as reduced particulate matter and improved public health outcomes. These are worthwhile goals.

How to get there?

We have the technical know-how to meet our goals. We also know that the accumulated costs of the energy transition will be tens of billions of dollars. What we need now is to update the processes for determining where, and how, infrastructure is built.

Several Northeast states have already taken this head on, or have started to. In New Hampshire, the legislature is considering two bills (SB 451 and HB 609), one seeking to streamline the administrative work of the state’s Site Evaluation Committee (SEC) and another to create a fast-track process for existing generating facilities to repurpose their locations with new technology.

In Massachusetts, Gov. Maura Healey appointed a roughly 30-person Commission on Clean Energy Infrastructure Siting and Permitting (CEISP) which was charged with finding ways “to swiftly remove barriers to responsible clean energy infrastructure development.” In late March, the group issued a 79-page report of recommendations that include clearer definitions of renewable energy infrastructure and shortening the amount of time it takes for a project to receive its approvals. The report followed legislation filed by the co-chair of the Massachusetts’ legislature’s Joint Committee on Telecommunications, Utilities and Energy, Jeff Roy, which also sought shorter permitting timelines. Both the Commission’s report and Chairman Roy’s proposed legislation recommend clearer definitions of what should quality for clean energy infrastructure.

It may seem strange that there needs to be a clearer definition of “clean energy infrastructure.” But the truth will surprise you – two battery projects in Massachusetts were blocked for years in part because of confusion and disputes about which governing bodies have authority to grant its permits.

Across New England, siting laws need updating to reflect new technologies and resource types, as well as the profound urgency to build a whole lot more infrastructure in the next 30 years than we have in the last few decades. Overall, this comes down to predictability of process and certainty in timelines. Those are old truisms for doing business in any segment of the economy.

But the hard truth is that, here in New England, we need to build a lot more, a lot faster. That means shorter timelines and a process designed to get to “yes.”

The need for shorter timelines should be clear: Time is money. In Massachusetts, it can take more than four years for a project to receive its necessary permits before it can start construction – and the work to prepare for those permits starts years before any paperwork is filed. The longer those projects take to permit, the more uncertainty the developer faces, which means higher costs overall.

Governor Healey’s siting commission eventually recommended a goal of an 18-month long process, recognizing it to be an ambitious goal. For a developer deciding where to direct its finite capital, an early “no” is better than a drawn-out “maybe” with years of litigation.

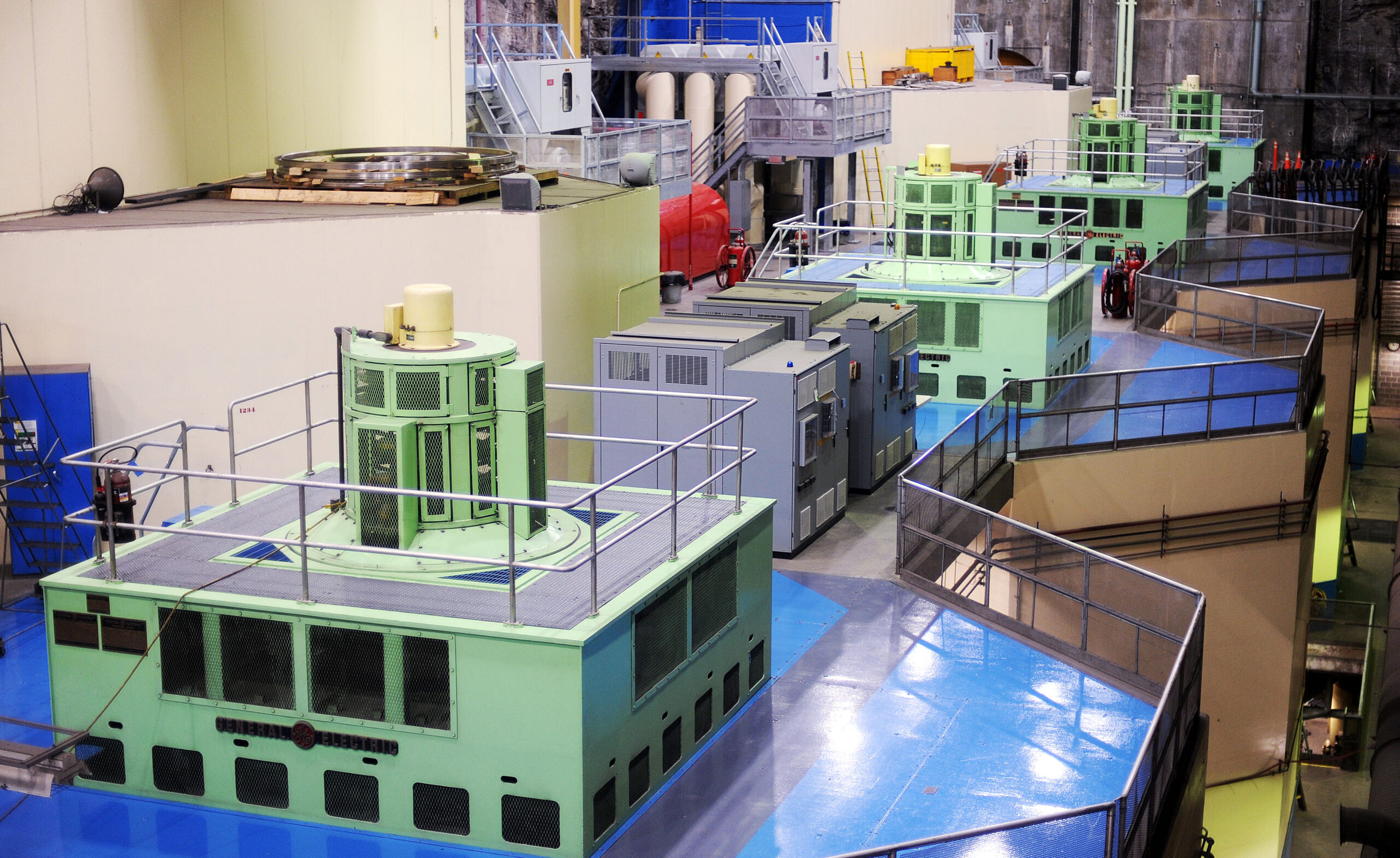

The interior of Northfield Mountain Pumped Hydro Storage Station, New England’s largest energy storage facility. The region needs to build significantly more infrastructure to meet its decarbonization goals.

But for those who may host such a project in their community, a shorter timeline can feel like an attempt to undermine their legitimate ability to protect their interests. There is no doubt that some of the infrastructure upon which we depend was built before national and state laws like the Clean Air Act, the National Environmental Policy Act, and the Clean Water Act were contemplated, or the term “Environmental Justice” was even conceived. We need to do better. And, in many states, it is not merely hope, but settled law, that we must do better for disproportionately impacted host communities.

To that end, many of the proposals across New England include paths that would provide increased opportunities for input from local communities as well as resources to help them participate.

At the heart of many of the stories of opposition, the so-called Not-In-My-Back-Yard-ism (NIMBY-ism) is a feeling in communities both rich and poor, urban and rural, that they didn’t have a say in what is happening and that what they sacrifice – be it for a solar panel, a battery storage facility, or a substation – is not worth whatever they receive in return.

That makes sense. The energy world is a complicated one – some companies get cost recovery, some don’t; some can use eminent domain, others don’t; some are federally regulated, others are state-regulated; some have good customer service, others are listed the worst in the country. For every project, there is a local process, a state one, and in some cases, a federal one. Even people in the energy industry can become confused about who does what in the energy industry.

Amid that financial and regulatory complexity, it can be hard for any single local community to see the tradeoffs between allowing a facility to be constructed or not, or to feel that they are anything other than a small cog in a big regulatory and corporate machine. This is why a clearer permitting process benefits not only developers, but host communities.

In the end, when clean energy infrastructure is built, it is not only the company building the project that benefits.

It is all of us: Our environment is cleaner and our public health outcomes improve. Consider, when someone drives an EV instead of an internal combustion engine vehicle – or an entire bus fleet runs on electricity instead of diesel – it is not only car owner and the bus rider who benefits. All of us do, because we no longer have to breathe in the exhaust fumes, and the deeply interconnected environment upon which our lives depend is cleaner.

Investments in electrification and the grid enable all of us to invest in a better future.

But all too often, when energy infrastructure is proposed, a black-and-white narrative appears: Winners and losers, nothing in between. And around the complex regulatory proceedings that determine the outcome of these projects, a cottage industry has popped up for those who litigate these projects to death. In the end, the economics are clear: Attorneys and advocacy groups earn money for blocking, not supporting, infrastructure. The real losers are those of us who are not able to access the cleaner, reliable grid our laws demand.

Local communities can benefit from hosting infrastructure. To be sure, construction can be disruptive. But the eventual projects also raise tax revenue for schools, emergency response, and other necessary services without burdening the local taxpayers. There are also direct local jobs for the trades and the knock-on benefits for the businesses that workers patronize.

Too often, though, vocal minorities loudly argue that this critical infrastructure should be built “somewhere else,” or “not here.” In New England, a thousand arguments that projects should be sited “somewhere else” have resulted in projects sited “nowhere.”

This is ironic. But it will eventually change, because the scale of construction we will need in order to keep our grid reliable amid increasing electrification will require just about every community to be a host community. And that’s appropriate, because we will all benefit from a more reliable, more resilient, cleaner energy grid.

Before we can get to that better grid, states across New England need to get some of the siting reform changes over the finish line. From there, it will be up to energy companies and policymakers to collaborate in getting projects proposed, sited, and into operation to truly shift New England’s economy to relying on a clean, cost-effective, and reliable electric grid.