The goals of energy policy are often likened to a three-legged stool that must always be in balance: reliability, cost, and environmental impact. The three are interdependent — pull out one leg, and the stool (along with the poor person sitting on it) will fall over.

In New England, environmental protection and climate change have long been the focus of policymakers, a point of great pride. But across the region, the “cost” leg is becoming an increasingly frequent discussion topic in energy circles — so much so that one governor recently said that affordability should be ranked ahead of environmental considerations right now. This evolving public discourse illustrates the challenges of transitioning to a cleaner grid and the need for everyone — generators, utilities, and policymakers alike — to sharpen their pencils to find the most efficient ways to achieve our carbon-reduction goals.

Connecticut has seen perhaps the loudest and harshest public outcry regarding costs. Anger began to mount there in early August, after consumers started receiving higher bills after using their air conditioners to get through the hottest July on record. That (understandably) very high electricity use coincided with the first month of new, higher rates. The situation was compounded a few weeks later, when the Public Utilities Regulatory Authority (PURA) approved additional bill increases for the major utilities in the state. Starting September 1, all-in rates in CT were more than 32 cents/kWh.

The response was fast and bipartisan. State Republicans called for a special legislative session to try to address the high costs, and a group of moderate Democrats, largely previously uninvolved in energy issues, announced that they wanted to hold hearings on the issue. Gov. Ned Lamont (D) said he would consider a special session, if lawmakers offered concrete proposals that would meaningfully reduce electric bills in the short-term. Outside of government, a petition started by a private citizen received more than 60,000 signatures calling on Lamont and the PURA Chair to eliminate certain costs from utility customers altogether. Largely in response to public sentiment over prices, a few weeks later, Lamont indicated that the state would likely not go forward with a long-anticipated offshore wind procurement and said he was the reason a wind project fell apart late last year, telling the Hartford Courant, “I just thought it was too expensive.”

Six weeks later, air conditioner use is down, and so are tempers, but the cost leg of the stool remains a focus of conversation and will undoubtedly come up in legislative proposals when lawmakers convene in January. And Connecticut isn’t alone.

In fact, in Rhode Island, legislation has already been announced in response to a recent rate increase that prompted uproar. During the public hearing regarding that rate increase at the state’s Public Utilities Commission, members of the public cried, shouted, and swore because of the cost of their electric bills, according to PUC Chair Ron Gerwatowski, who described the hearing at a recent meeting in Boston. “There is no question that affordability is being strained today,” and that consumers are likely to continue to experience high electricity costs going forward, Gerwatowski said.

In Massachusetts, lawmakers failed to pass a major energy bill this summer in part because a key legislator in negotiations expressed concern about the rising cost of electricity — and the issue of affordability remains a matter in ongoing negotiations. In Vermont, Gov. Phil Scott (R) is concerned that a new state law to decarbonize the heating sector will cost more than consumers can afford. In Maine, costs related to distributed solar are a source of controversy, with some large consumers saying costs are so high they could drive them out of business. And New Hampshire has claimed that its rates are lower than other New England states due to policy choices. While that assertion is disputed, it is clear that cost is a major driver in the Granite State’s elections this year, with one candidate openly criticizing Massachusetts for its renewable energy policies (Kelly Ayotte’s slogan is, “Don’t MASS up NH!”).

The causes of the rate increases in the states are different – as Chair Gerwatowski said recently, there is no one single reason why New England’s electricity rates are so high. That means there’s no single, simple way to lower them. Regardless of the complexity and diversity of the causes, the fact is, elected officials, regulators, and consumers are becoming increasingly concerned about energy costs — in a region already known for high costs.

At the recent event in Boston, New England regulators offered some solutions. They include ensuring the most vulnerable are cared for and allowing time-of-use rates, which would make consumers more sensitive to wholesale pricing and the true cost of electricity. Noting that one controversial solar incentive paid a flat rate to participants, Maine Commissioner Carrie Gilbert noted that, to the degree possible, it would be preferable for future programs to include competition to lower prices.

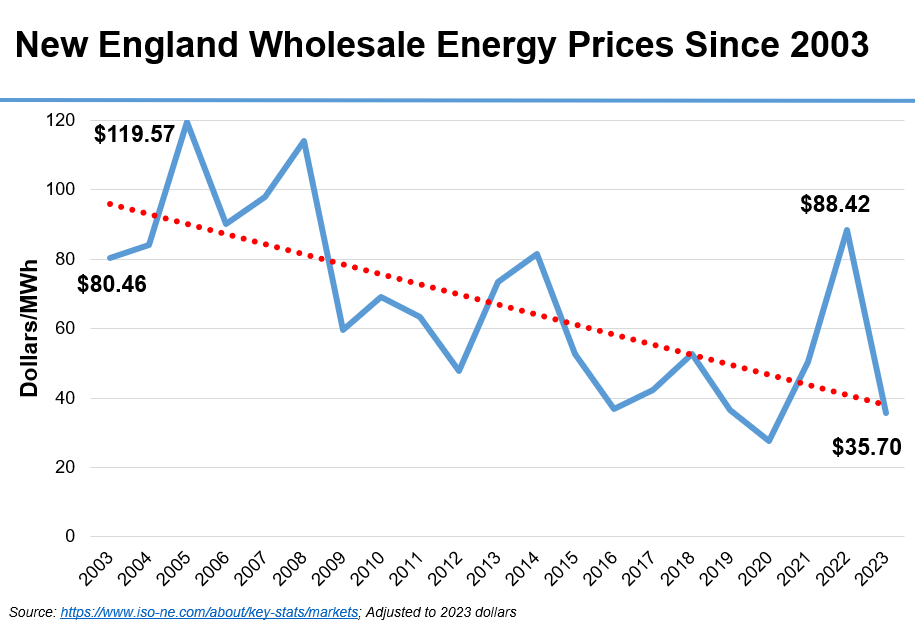

At NEPGA, we agree that competition can have a downward pressure on prices and point to the overall trending on the cost of generating electricity in New England since the introduction of markets around 20 years ago.

(![]() Shameless plug: To help people better understand their bills, NEPGA, in partnership with others, recently launched https://whatsinmyelectricbill.com/, which allows Massachusetts electricity customers to see what, exactly, goes into their electric bills and how that has evolved since 2010. With continued support, the website will eventually include other New England states.)

Shameless plug: To help people better understand their bills, NEPGA, in partnership with others, recently launched https://whatsinmyelectricbill.com/, which allows Massachusetts electricity customers to see what, exactly, goes into their electric bills and how that has evolved since 2010. With continued support, the website will eventually include other New England states.)

There is little doubt that overall consumer electricity bills will continue to trend up. The reasons are varied; they include investments in supporting the “reliability” and “environmental” legs of the stool with transmission and distribution system improvements that will cost tens of billions of dollars, if not more. (National Grid plans to spend $35 billion in New York and Massachusetts alone.) In addition to more transmission and distribution infrastructure, New England will also need  additional power generating facilities as well as ongoing maintenance of existing facilities.

additional power generating facilities as well as ongoing maintenance of existing facilities.

With such great investment looming, it makes sense to foster competition in as many areas as possible. Well-regulated, competitive markets foster innovation, provide transparency, and generally drive down costs. While New England’s wholesale electricity markets may be volatile year-to-year, they have nonetheless driven down the costs related to generating electricity since their inception. That has then freed up resources to invest in other areas of the electric system, such as transmission and distribution.

It also makes sense to maximize the efficient use of our current infrastructure. Right now, nearly half of New England’s energy annual electricity demand is met by non-emitting resources. These resources, combined with dramatic increases in efficiency in operations at fossil-fuel-powered plants, have enabled New England’s power plants to reduce emissions by about 50% since 1990.

The region’s existing generators are the foundation on which the clean-energy future will be built, and the new renewable resources the New England states are pursuing — such as offshore wind and solar —will add to, not replace, many of our existing generating facilities. If we let too many of our existing resources retire prematurely, we risk compromising all three legs of the energy stool: Cost, reliability, and environmental impacts.

There are a variety of ways that states can try to ensure the grid remains reliable and prices are as competitive as possible while continuing to reduce carbon. For example, to strike the balance between fostering new resources and preserving existing ones, we have long argued that the New England states should build on their history of collaboration to enhance existing wholesale markets. We also believe that the New England states each need to update their siting laws to make it easier and less risky to build energy infrastructure over the next decade.

Achieving economy-wide decarbonization while keeping the energy stool in balance will require effort and creativity, but, quite simply, it has to be done. As Massachusetts Commissioner Staci Rubin recently said: Just because something is hard doesn’t mean we shouldn’t be doing it.