This summer, everyone who works in the energy industry will get the same question at barbecues, picnics, and baseball games: Why is my electric bill so high? It’s a good question. The short answer at parties is usually, It’s a long story. Pass a hot dog.

For us nerds in the industry, the question is actually bigger than, Why are bills so high? For us, it’s this: Why are consumer bills so high when the cost of generating electricity has been so low?

But if we had time to explain, and the interlocutor had the patience, this  is what we’d share.

is what we’d share.

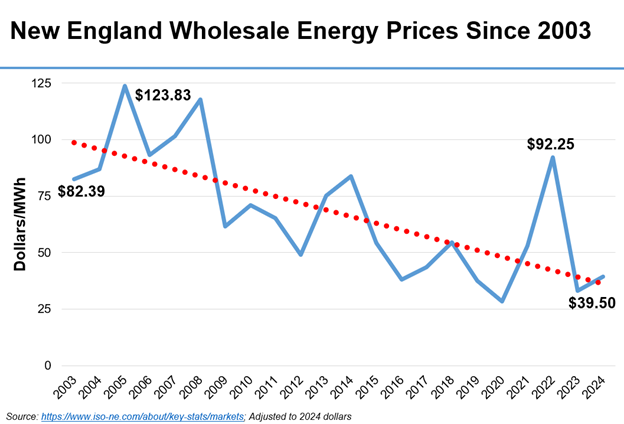

As you can see, 2024 saw the third-lowest wholesale electricity prices in ISO New England market history. Only 2020 and 2023 were lower. The wholesale markets are working as they were intended: Providing reliability at the lowest cost.

And yet, New England’s consumers’ bills are going up – including even the supply portion of those bills. There are many reasons for this disconnect between the cost of generating electricity and the total costs that consumers see on their bills.

Here are some, but not all of, the reasons.

1.) Uncertainty drives retail prices up.

Most retail customers don’t buy their power directly from the wholesale markets. Instead, they rely on their utility, which in turn contracts with a third-party competitive supplier to do the buying and selling on their behalf. (This energy service is called different things in different states. In Massachusetts, it’s called “basic service.” In New Hampshire, it’s “default service.” In the end they’re basically the same products with different names.) The laws and practices vary from state to state, but for the most part, the contracts between the utilities and the suppliers cover a six-month period and set a fixed price for all customers who don’t choose to get their energy from another provider.

In turn, the supplier handles all of the buying and selling and hedging in the wholesale market. There are lots of analogies for this, but our favorite involves a farmer, a grocery store, and a consumer. The price of eggs can actually be quite volatile, especially in recent months. So, too, with electricity. A farmer (power plants) sells eggs (electricity) to a supplier (grocery store), and the grocery store agrees to sell the eggs to consumers (families, businesses) at the same price for six months. With electricity, the third-party competitive supplier cannot change its prices once the contract starts, even if the price in the market drops lower or surges higher than the fixed price. This shields the consumers from day-to-day market volatility.

Volatility is often driven by factors that no one can really control. Some variables are about the cost of the supply of electricity. What will the cost of fuel be? What will the weather be like? What geopolitics might affect supply?

On the other side of the equation is demand: Just how much electricity will people need from the grid?

When a supplier (grocery store) calculates its costs, it needs to account for all of these but still come up with a single cent-per-kWh price for all possible customers.

More on volatility

In recent years, two state policies have had unexpected impacts on the amount of demand energy suppliers need to meet: the growth of solar installations and community aggregation.

Regarding solar: New England’s grid has become increasingly reliant on nearly 400,000 different solar arrays with a cumulative generation capacity of more than 7,600 MW of electricity, all of them highly dependent on weather. If a customer’s solar array isn’t producing, then that customer needs power from the grid – and the supplier needs to account for that increased, but transient, demand. Now multiply that uncertainty by 397,105 arrays, and you have a sense of the statistics that underpin the challenges of forecasting demand. By 2034, ISO-NE expects the total solar capacity to nearly double from 7,600 MW to 14,343  MW, thus increasing the complexity of the demand that needs to be served by the grid.

MW, thus increasing the complexity of the demand that needs to be served by the grid.

Regarding aggregation: Some states, such as New Hampshire and Massachusetts, are home to fantastically popular community aggregation programs. Through these programs, a city or town decides not to use the utility’s six-month supplier. Instead, the city bundles all of its consumers into a single group and then works with an electricity supplier to buy the community’s power separately from the utility-administered default supply.

Community aggregation often works well because a municipality has more flexibility (mostly regarding the duration of its contracts) than a utility does, and can sometimes use that flexibility to negotiate a better price. When communities sign up for these programs and move away from the default/basic service provided by their utility, they still have the ability to return to the utility service at any time, for whatever reason. The utility, as a supplier of last resort, cannot say no if the community wants to come back.

While these aggregation programs have had successes, there have also been plenty of times that the default supply is a better deal. If that happens, the utility’s supplier must now service that town’s demand at the negotiated default service price – even if the town wasn’t part of the deal when the six-month contract was signed.

A community needn’t even be that large to make a difference. Consider Waltham, Mass, which is one of many cities on an aggregation plan. If it returned to basic service, there would be more than 20,000 additional households to account for. But this can also happen on much larger scales, as even the city of Boston is an aggregation community.

For the suppliers, even if the risk that a town would return to basic service is low, that risk still needs to be accounted for in its price.

More risk = higher price.

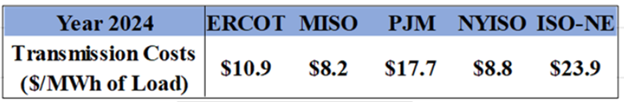

Transmission costs across Regional Transmission Organizations (RTOs). Source: Potomac Economics

2.) The cost of moving electricity from the generator to the customer has increased.

Since 2004, the cost of transmission in New England has risen by more than 900%.

Ultimately, utilities receive a more-than-10% ROE for all of their transmission investments. They are doing what they’ve been incentivized to do. But it is also true that New England is a pretty stark outlier in terms of the pace of increases and the overall costs for consumers. Forecasts indicate those costs will only increase and not decrease anytime soon.

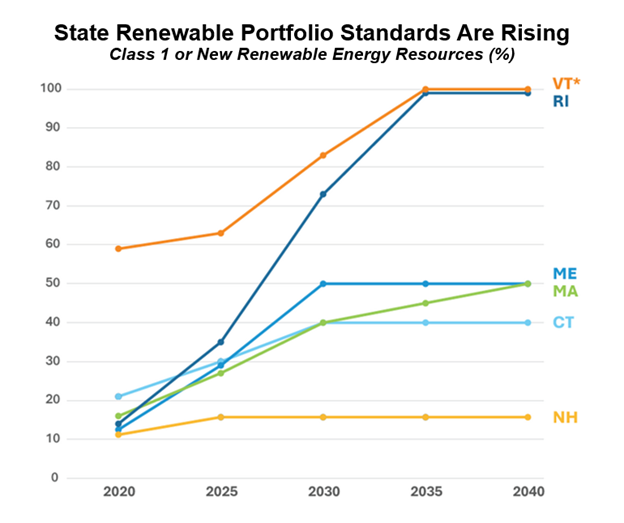

3.) Renewable Portfolio/Energy Standards and other clean energy prices are increasing – by design.

Source: ISO New England

Each New England state has a requirement that utilities meet a certain percentage of their load from renewable or clean resources by a date certain.

Compliance doesn’t involve the physical procurement of power produced by renewable energy facilities. Instead, electricity providers meet the requirements by purchasing renewable energy certificates (RECs), which represent 1 MWh of renewable energy generated and delivered to the electric grid. These renewable programs can also be met by making alternative compliance payments (ACPs), which function as both a price ceiling and stick if REC shortages occur. The money from the ACP is usually intended to support the development of new renewable energy projects. In turn, these projects generate RECs, theoretically helping to ameliorate the tightening market.

New England is home to some of the most aggressive renewable energy goals in the United States. Consider Rhode Island. The Ocean State first established its Renewable Energy Standard in 2004. At that time, the goal was to achieve 16% renewable energy by 2019. It was updated in 2016 with a target of 38.5% renewable energy by 2035. Most recently, in 2022, the goal was increased to 100% by 2033.

However, REC markets are facing limitations with the slow-down of certain renewable energy projects, such as offshore wind, which means there are fewer RECs to buy, even though the demand is increasing. In some states, that shortage of supply comes as the price of ACPs has been increasing. (For example, see Rhode Island’s ACPs.)

The Renewable Portfolio/Energy Standards are not the only decarbonization programs focused on electricity. For example, the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI) is a cap-and-trade program that requires power plants to purchase allowances for each ton of carbon dioxide they emit. In addition to RGGI, Massachusetts has its own carbon price, implemented through the Electricity Generator Emission Limits program (EGEL).

In 2023, taken together, RGGI and EGEL added about $690 million to  total energy costs in New England, according to ISO New England’s Internal Market Monitor. Each additional program adds costs, compliance risks, and complications beyond just producing the most efficient, lowest price energy for a household.

total energy costs in New England, according to ISO New England’s Internal Market Monitor. Each additional program adds costs, compliance risks, and complications beyond just producing the most efficient, lowest price energy for a household.

Those programs have been enacted for virtuous reasons, but there are consequences, particularly as states get more and more prescriptive in seeking specific technologies and resources. There may be individualized costs for renewable energy compliance, carbon emissions, energy efficiency surcharges, and funding of state-mandated contracts. In Connecticut, these programs are lumped together into a “Public Benefits” charge, which now makes up roughly 20% of a residential consumer’s bill.

In the end, there’s no silver bullet. Maybe silver buckshot?

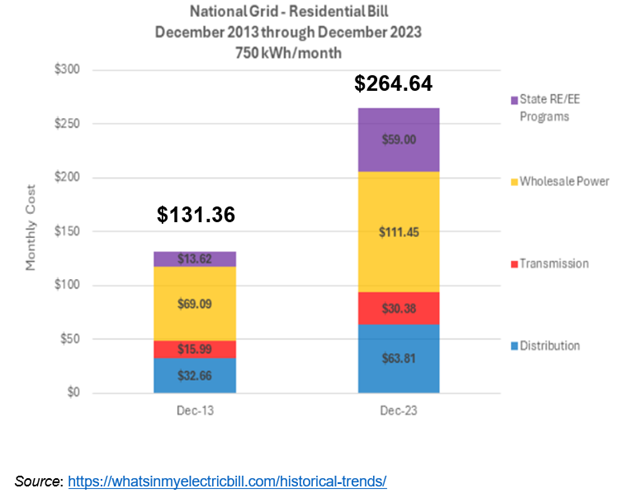

A recent analysis of a typical Massachusetts bill shows that every aspect of consumer bills has increased since 2013. While the analysis focuses on Bay State bills, its trends are mirrored across New England.

As the concerns regarding energy affordability continue to grow, it is clear that policymakers will be focusing on every part of the bill – Massachusetts Gov. Maura Healey recently introduced legislation to address affordability, and the Connecticut legislature this year passed a bill to reduce some ratepayer costs. And there will be much more to come throughout the region.

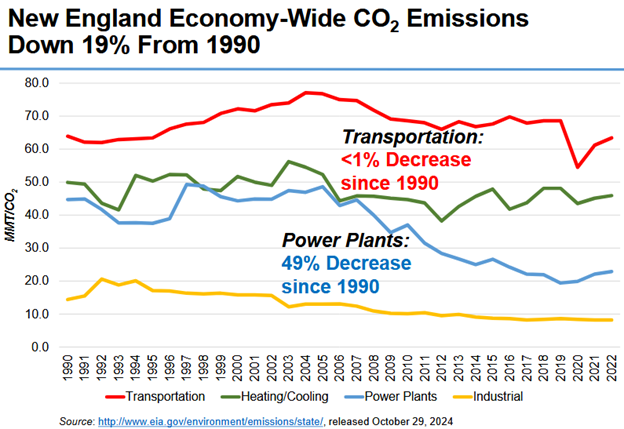

These conversations may not be easy ones. But New England also has some points of pride – New England has already made great progress in emissions reductions from power plants, boasts one of the most efficient power generating fleets in the United States, and has a strong track record of reliability.

So this summer, when you’re at a barbecue and someone asks, “Well why is my electric bill so high?” you can send them this post. We know that won’t make the indigestion disappear on its own, but the generator community remains committed to be a part of the solution to the growing focus on affordability in the region and the nation.